LEKË DUKAGJINI (1410-1481)

Lekë Dukagjini is a quite complex historical figure. Furthermore, this figure has also taken dimension of a myth, if the term is accepted when our National Hero Gjergj Kastrioti-Scanderbeg is regarded.

Lekë Dukagjini (1410-1481) was contemporary with Gjergj Kastrioti (1405-1468). History has known both of them as hereditary princes, who were heightened when they took reins of their respective homonymous princedoms: Leka – the Dukagjnini’s, when his father, Pal Dukagjini died, (1446) and Gjergj – the Kastrioti’s, eight years after his father’s, Gjon Kastrioti, death (1443). Dukagjini’s Princedom, with Lezha as its own capital city, included Zadrima, the areas in north and northeast of Shkodra and was extended in remote areas of present Serbia, having Ulpiana, near Prizren, as e second capital city. On the other hand, Kastrioti’s Princedom, with Kruja as its capital, included Mat and Dibra region, reaching Rodon Castle on the Adriatic coast. Since before coronation Lekë Dukagjini had gained a comprehensive education under the spirit of Europian Renaissance in cities like Venice, Raguza or Shkodra; meanwhile Scanderbeg had achieved a fast and splendid military career in the Sultan’s court of Istanbul. Leading the Lezha League (founded in Lezha in 1444) Scanderbeg sow Leka (initially his father Pal Dukagjini) beside him. They fought side by side (sometimes they opposed each other) until Scanderbeg died (1468). Lekë Dukagjini continued his deed leading Albanians in most difficult period of their anti-ottoman resistance, till the end of his life (1481).

Chroniclers and historians, beginning from contemporary Tivarasi/ Biemi, Frëngu, Barleti e Muzaka, up to Gegaj and Noli of 20-th Century, when enlightening the deeds of Gjergj Kastrioti, have rightly mentioned Lekë Dukagjini and other princes of that time. But we cannot say that they are right when groundlessly defamed Lekë Dukagjini, only because were enchanted by the by the main figure, Scanderbeg. Those anonymous, authors of myths have been more balanced. They identified Scanderbeg with a dragon-prince that, dared to fight and always to win against the monster, while they depicted Lekë Dukagjini as angel-prince, who, with courage and wisdom safeguards the continuity of Albanian cause.

Lekë Dukagjini was the most powerful Albanian prince after Scanderbeg. That is why his name became objective of intrigues by Venetian policy (and history) until La Signoria felt the risk from High Gate coming to the doorstep and really joined its forces with the Albanian resistance, declaring war to Ottoman Empire (1463). After that the Venetians ceased defaming Lekë Dukagjini. Its historians wrote for some deeds of Lekë Dukagjini, beside Scanderbeg until his death (1468) and later leading the Albanian troops beside Venetian forces until the sign of peace by Signoria and High Gate (1479). Afterwards they kept silence. Legend informs us that Lekë Dukagjini continued the resistance leading brave people of Princedom until his death.

The historians have defamed the name of Leke Dukagjin since the beginning, looking at him an antagonist personality to Scanderbeg, in order to make their stories about Scanderbeg, who was the only Albanian Hero, who Europe knew in the successful battles of Albanians against Ottoman invasion, more intriguing; but also because these historians refuse to blame Western Europe for not organizing an antiottoman coalition in the Balkans. They didn’t dare to judge especially the Republic of Venice, which not only didn’t stand allied to the Albanians when they were confronting an whole empire which was threating Europe, but made use of Albanian resistance for its commercial interests, intriguing to divide Albanian princes, making them confront each other with arms, or, when this was not possible, declaring them enemies of Venice and even of Christianity. Lekë Dukagjini was the most powerful and authoritative prince, second only to Scanderbeg; that is why he became objective of intrigues by the Venitian policy (and historians), until Signoria felt the Ottoman threat coming to its gate and joined forces with the Albanian resistance, declaring war to Instambul (1463). After that year the Venitian defamation towards Lekë Dukagjini was ceased. In the meantime historians described some deeds of Lekë Dukagjini beside Scanderbeg until Scanderbeg died (1468) and later leadindg Albanian troops in battles side by side with Venitian forces, until Venice made peace with High Gate (1479). Afterwards historians were silent. The legends inform us that Lekë Dukagjini continued his resistance until his death.

But defamation towards Lekë Dukagjini’s name has continued even after his death, as the resistance in his Princedom and more extensively continued. The defamation after death has to do with his work Kanun, that Lekë Dukagjini left as inheritance to his subordinates, Albanians. The essence of Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini are his sentences kept and enriched generation after generation for nearly six centuries. This Homeric phenomenon has raised his name to a legend, turned it in a genuine myth, to a degrre that make difficult for scholars to accept it as e historical reality. That explains why some of them have continued to defame Lekë Dukagjini’s name and his Kanun, as happened to Homer and his Iliad and Odyssey. (For similarity: even to Lekë Dukagjini was invented a blind brother). But the time and circumstances when the sentences of Kanun were conceived can be enlightened analysing documented biographical facts for Lekë Dukagjini.

By the end of 50-ies of 15-th century, Dukagjini Princedom had not any more any of its developed centres: Lezha was surrendered to Venetians (1393), Ulpiana, the capital of Princedom was destroyed to the soil by the Turks, since before Prizren, a developed centre of Princedom, was surrendered to them (1458). Under those circumstances Lekë Dukagjini seized the fortress of Shati in Zadrima, intending to have it as his princely residence, but he was attacked by Skanderbeg, who handed it back to Venetians. Without a princely residence and, for some time, being amidst three fires (Turks, Venetians, Skanderbeg) Lekë Dukagjini found shelter in the hinterland of Highlands of his Princedom, where he constructed fortresses and castles togother with the free inhabitants of those areas, who warmly welcomed and respected their overlord of Dukagjini Family, his lady, Teodora of Muzakaj from Berat and all his court. With highlanders of Princedom, well-known for their bravery, Leka, not only rebuilt his castle-towns, but to ensure to himself a permanent source for a sufficient army, which played an important role within framework of Lezha League Army under Skanderbeg in command and even later. In exchange Lekë Dukagjini guaranteed to the highlanders of the Princedom and to everyone who, especially after the death of Scanderbeg, joined him for procuring a defence to himself, freedom within their tribal organisation, which he, under the circumstances, raised to the institutional level by reorganizing the Councils of Elders on village and region basis. Kanuni got conceived during this period (1458-1481), when he leaded all the popular assemblies and Councils of Elders and was inherited generation after generation as a practice of judgement and, using sentences formulated by him or restated case by case, as juridical sentences. Kanun, remained unwritten, but was acting in centuries as English “Common Law” acted, until was gathered and codified by Shtjefën Gjeçovi during replacement of 19-th with the 20-th century.

When Gjeçovi was working on the gathered canon material, Kanuni, as its author were sanctified by all the Albanians, regardless their religion. The name of Lekë Dukagjini was not defame by the people; on the contrary, it was hightened to a hero’s level. The fact that a ruler turned to become a real, popular and national hero, could be explained by the theory which sustains that common people, accepting their rulers or knights as their heroes, “identified themselves with values of the leader and of the nobility, or, at least, because they needed to structure their world through models offered by the ruling group” (P. Burke: 169)

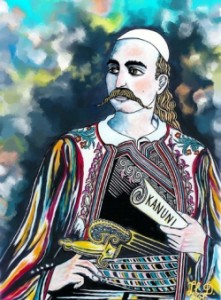

Kanuni of Lekë Dukagjini is an unique work in Albanian with the humanist spirit of European Renaissance period, which, despite the fact that was and still is defamed, remains valuated highly by serious scholars, both Albanian and foreign as an “monumental work” (A. Buda/ Gjeçovi-Kryeziu: 22), “contribution in the treasure of world culture” (C. Von Scherwin/Hylli i Dritës 1929: 502) and its author, Lekë Dukagjini is qualified a “imposing personality” (Edith Durham: 116 and “National Hero” of its people. (J. Hahn: 114) A lot of writers and artists dedicated their works to him; among them the novelist and poet Ditëro Agolli (“Wife, for you I fought with Lekë Dukagjini”, poetry), the Arbëresh dramatist Anton Santori (“Alessio Ducagini”, melodrama, written between 1855-1860, published in 1983), the painter Naxhi Bakalli (“Kuvendi i Dukagjinit”, tablo on the wall 4×3,2m in Burrel Historicaly Museum), the painter of Kosovo Engjëll Berisha (“Rrënjët e Dukagjinit”, vizatime 1950-1956), the painter Simon Rrota (Lekë Dukagjini, portrait-Art Gallery, Shkodër), the sculptor Sotir Kosta (“Lekë Dukagjini”, portrait in bronze in National Museum of Scanderbeg, Kruja, 1982) ect.

As apocrypha of Lekë Dukagjini is accepted the portrait of Simon Rrota (1887-1961), which introduce the author of Kanun in frontal view, having a sharp look, in which are joined together intelligence and wisdom, wearing the traditional waistcoat of costume of Albanian highlanders and a sword, holding a manuscript of Kanun in his left hand, which reminds the humanist intellectual of 15-th century. “An extraordinary personality”, Lorenzo de Medici, with whom we wanted to compare Lekë Dukagjini since the beginning of this biography, was mentioned as “a genial politician, who could see the difference between the genuine power and its appearance”. In the cover of his book he is depicted in the streets of Florence dressed as an ordinary citizen, encircled by girls singing his ballads… Lorenzo was really a good poet and the most generous patron of poets, scientists, and philosophers” (K, Clark: 106). To some extent, we can imagine like that even Lekë Dukagjini, whose poetry would be his sentences of Kanun. If this comparison, as every other comparison, would not be accepted, we, at least, can compare the Dukagjini Princedom with the small courts of Northern Italy in the last quarter of the 15-th century, to whom “the Renaissance owes nearly as much as Florence” (K. Clark: 107). In this case Leka could be compared with Duke of Urbino, Frederigo Montefeltro, who “was not only a man of extraordinarily learning and cleverness, but also the greatest strategist of his time, who managed to defend his possessions from surrounding criminals. He was a passionate collectioner of books and, in his valuable portraits, he is depicted reading one of his manuscripts. He is wearing armor and other military equipment… His palace was initially being built as an fortress on a insurmountable rock and only later, after having procured safety, was given this soft and refined look, which made of it one of most beautiful architectonic monuments in the world” (K.Clark: 107).

We are able nowadays to restore neither a castle nor a princely palace of Leka Dukagjini; far less we can evaluate what does not exist with superlatives:” the most beautiful in the world, in Mediterranean, or in the region”, because by that time ” Albania was cancelled from the list of independent countries… every link with Europe was interrupted. Castles and flourishing cities… with palaces and monuments… were disappeared from the earth… remained as shadows of the ancient splendour. (F.S.Noli: 591-592). But Kanuni of Lekë Dukagjini is really the most important monument of Albanian culture during period of European Renaissance, which has lived for 6 centuries, playing such a extraordinary role in the life of the nation, of whose language is written.